2015-9

An Exploration of the Perspectives of Young Males with Regard to their Experience of non-Heterosexual Sexuality Transitions and the Potential Influences on this Transition within an Irish Context

Caroline Kelly

Technological University Dublin

Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/aaschssldis

Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons

Recommended Citation

Kelly, Caroline (2015) An exploration of the perspectives of young males with regard to their experience of

non-heterosexual sexuality transitions and the potential influences on this transition within an Irish

context. Masters Dissertation, Technological University Dublin.

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Social Sciences at ARROW@TU Dublin. It has

been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more

information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected],

[email protected].

2015-9

An Exploration of the Perspectives of Young Males with Regard to their Experience of non-Heterosexual Sexuality Transitions and the Potential Influences on this Transition within an Irish Contex

Caroline Kelly

Technological University Dublin

Follow this and additional works at: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/aaschssldis

Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons

Recommended Citation

Kelly, Caroline (2015) An exploration of the perspectives of young males with regard to their experience of

non-heterosexual sexuality transitions and the potential influences on this transition within an Irish

context. Masters Dissertation, Technological University Dublin.

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open

access by the Social Sciences at ARROW@TU Dublin. It

has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an

authorized administrator of ARROW@TU Dublin. For more

information, please contact

[email protected], [email protected],

[email protected].

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons

Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 License

An exploration of the perspectives of young males with regard to their experience of non-heterosexual sexuality transitions and the potential influences on this transition within an Irish context

A thesis submitted to the Dublin Institute of Technology in part fulfilment of the requirements for award of Masters in Child, Family and Community Studies

Caroline Kelly

September 2015

Supervisor: Ann Marie Halpenny

Department of Social Science, Dublin Institute of Technology

Declaration

I hereby certify that the material which is submitted in this thesis towards the award of the Masters (M.A.) in Child Family and Community Studies is entirely my own work and had not been submitted for any academic assessment other than part fulfilment of the award named above.

Signed:

Date:

Acknowledgements

Firstly, I would like to acknowledge and wholeheartedly thank the seven participants who took part in this study. I extend great admiration and appreciation for your openness and honesty in sharing your experiences. This research would not have been possible without your truly valuable input.

I would also like to thank my supervisor Ann Marie Halpenny, for your continued advice and guidance. I express my sincere gratitude for your patience, commitment and encouragement.

To my loving family, thank you so much for your kindness, patience and never ending support. To this day I don‟t know how you put up with me.

Last but not least to my amazing friends. I‟m so lucky to have such a wonderful group of people around me. Your reassurance, understanding and advice knows no bounds. You helped keep me smiling throughout this process.

Glossary of terms

Social Context –

For the purpose of this research „social context‟ refers to the immediate physical and social setting in which people inhabit.

Social Networks –

Refers to people‟s personal relationships and social interactions.

Non-heterosexual sexuality transition –

refers to the process of recognising, understanding and integrating any sexual orientation that is not classified as „heterosexual‟.

Heterosexual –

refers to a person that is physically and emotionally attracted to a person of the opposite sex.

Disclosure or ‘Coming out’ –

refers to the process by which lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people openly declare their sexual identity, to themselves and others (Lalor, de Roiste and Devlin 2007, p.105).

Passing –

refers to the ability to be regarded as a member of a social group other than your own, that being heterosexual for non heterosexuals

Sexual minority –

Is used to encompass more diverse expressions of sexuality and gender variance, it includes self-identified gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender adolescence and youths who are gender-variant and/or experience same-sex attractions, relationships, and/or behaviours without necessarily labelling themselves (Elze, 2005).

Sexual Stigma –

refers to the shared belief by society in which non heterosexuality is disintegrated, discredited and constructed as invalid relative to heterosexuality (Herek, 2004)

Heterosexism

Is an ideology that perpetuates sexual stigma by denying and denigrating any non-heterosexual form of behaviour, identity, relationship or community (Herek, 2004).

Internalized homophobia –

refers to the personal acceptance and endorsement among sexual minorities of sexual stigma as part of the individuals value system and self-concept

Abstract

This research aimed to explore the perspectives of young males with regard to their experience of non-heterosexual sexuality transitions and the potential influences on this transition within an Irish context. A qualitative research approach was adopted, using semi-structured interviews with young males between the ages of twenty-five and thirty-two. This method allowed for the details of participants‟ lived experience and their individual perceptions to be captured. Key findings suggest that experiences of non-heterosexual sexuality transitions in both family and friendship contexts shaped how the transition was negotiated. Disclosure of sexual minority status to family members is still a significant issue for many individuals and can be met with a wide variety of responses. Despite negative initial responses the transition generally strengthened and positively impacted on family and friendship relationships over time. The overwhelming majority of sexuality related support was found to come from friends, with non-heterosexual friends in particular offing support in terms of understand and reassurance.

A significant finding of this research was the monumental influence social and historical context had on non-heterosexual sexuality transitions. The fact that heterosexist beliefs and values were reaffirmed constantly through cultural institutions meant that sexual minority issues were invisible within cultural discourse. This lead to isolation and stigmatisation. Individuals had very different approaches to coming to terms with their sexuality. These varying approaches stemmed from differences in personality, cognitive processes and coping mechanisms.

The individual nature and multiple influences on how non-heterosexual sexuality transitions are negotiated highlight the need to develop and explore inclusive theoretical frameworks that allow for variation in historical, cultural and psychological contexts. Interventions and practitioners working with sexual minorities should also consider the importance of recognising the unique challenges each individual faces and the specific supports that might work for them. This should limit the potential for making assumptions and generalizations about sexual minorities and help identify positive influencing factors which could be built upon.

Table of contents

Title Page

Declaration

Acknowledgments

Glossary of terms

Abstract

Table of contents

List of abbreviations

List of Appendices

Chapter One: Introduction and Overview

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Context of the study

1.3 Rationale for the study

1.4 Aims of the study

1.5 Outline of the Study

Chapter Two: Literature Review

2.1 Introduction

2.2 Perspectives on non-heterosexual sexuality transitions

2.3 The influence of social context on non-heterosexual sexuality transitions

2.4 The experience of non-heterosexual sexuality transitions within a family

context

2.5 The experience of non-heterosexual sexuality transitions within a friendship

context

2.6 The Risk and Protective factors associated with this transition

2.7 Conclusion

Chapter Three: Methodology

3.1 Introduction

3.2 Research design

3.3 Strengths and limitations of methodological approach

3.4 Sample

3.5 Research instrument

3.6 Pilot study

3.7 Ethical considerations

3.8 Data analysis

Chapter Four: Findings

4.1 Introduction

4.2 The experience of non-heterosexual sexuality transitions within a family

context

4.3 The experience of non-heterosexual sexuality transitions within a friendship

context

4.4 The influence of personality and personal traits on young people‟s sexuality

transitions

4.5 The influence of social context on non-heterosexual sexuality transitions

4.6 Self-identified risk and protective factors in relation to sexuality transitions

4.7 Conclusion

Chapter Five: Discussion of Findings

5.1 Introduction

5.2 The experience of non-heterosexual sexuality transitions within a family

context

5.3 The experience of non-heterosexual sexuality transitions within a friendship

context

5.4 The influence of personality and personal traits on young people‟s sexuality

transitions

5.5 The influence of social context on non-heterosexual sexuality transitions

5.6 Risk and protective factors associated with sexuality transitions

5.7 Reflection on the process of this study and conclusion

Chapter Six: Conclusions and Recommendations

6.1 Introduction

6.2 Conclusions

6.3 Recommendations

References

Appendices

List of Abbreviations

LGBT:

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender

GLEN:

Gay and Lesbian Equality Network

IPA:

Interpretative Phenomenological Approach

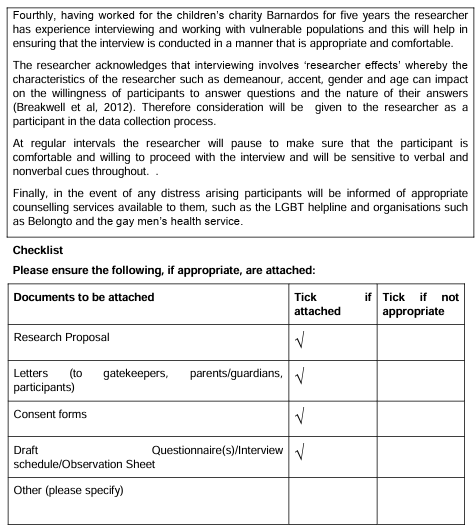

List of Appendices

Appendices:

Appendix A: Interview Schedule

Appendix B: Letter of invitation for participants

Appendix C: Informed consent form

Appendix D: Letter of invitation for gatekeepers

Appendix E: Ethical application from

Appendix F: Sample interview transcript

Appendix G: Sample coding

Chapter One: Introduction

1.1 Introduction

The study aims to explore the perspectives of young males with regard to their experience of non-heterosexual sexuality transitions and the potential influences on this transition within an Irish context. This chapter will provide an introduction to the study by first outlining the context of sexuality transitions in Ireland. The rationale and aims of the study will then be introduced followed by an overview of the subsequent chapters.

1.2 Context of the study

Only thirty years ago Irish society could be described as extremely homogenous, the overwhelming majority were Catholic and lived lives centred on traditional Catholic family values including traditional attitudes regarding gender roles (Norman & Galvin, 2006). Due to Ireland‟s past experience of colonialism and the strong hold of Catholicism, there was effectively a silence surrounding sexuality (Tovey & Share 2007). It was linked to concepts such as sin, control and danger and sexual expression was confined to heterosexual marriage (Moane, 1995; Inglis, 1998). These issues, alongside the Catholic Churchs‟ homophobic discourse, lead to the legal, economic

and social discrimination of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) people. Due to initiatives such as the Irish Gay Rights Movement (IGRM), the Campaign for Homosexual Law Reform and the work of Senator David Norris, strives have been made towards equality through the decriminalisation of male homosexual acts in 1993, and the prohibition of discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation under the Equality Act 2007 (Reygan & Moane, 2014).

Society has changed dramatically for sexual minorities in recent years (Barron & Bradford, 2007) and this change culminated in Ireland with the passing of the referendum on same-sex marriage which made Ireland the first country to approve same-sex marriage by popular vote (Irish Times, May 24th 2015). This campaign, while highlighting changing attitudes and societal acceptance for sexual minorities, also exposed underlying hetero-sexist ideologies, for example, same sex marriage disrupts the „normal‟ order of society due to it challenging definitions of the family.

1.3 Rationale for the study

The rationale for the choice in topic was due to a personal interest in the area and a

desire to explore how non-heterosexual sexuality transitions were negotiated at a time

of such significant social change for sexual minorities in Ireland. Recently many

authors in this area have highlighted the importance of examining the influence of

social, historical and cultural contexts in relation to sexuality transitions (Hammack &

Cohler, 2012), yet there is very little empirical Irish research which investigates these

influences. Research in the area of experiences within family and peer contexts is

growing (Goldfreid & Goldfreid, 2001; Savin-Williams, 2005) yet more qualitative

research is needed in light of changing attitudes and growing societal acceptance. It is

anticipated that giving sexual minorities a voice within the discourse on this transition

will allow for a deeper understanding of how the transition is negotiated. Finally, it is

hoped that the identifying of potential risk and protective factors associated with this

transition will help inform the work of practitioners and organisations working with

sexual minorities.

1.4 Aims of the study

The overall research aim is to explore the perspectives of young males with regard to their experience of non-heterosexual sexuality transitions within an Irish context. The objectives are to explore the potential influences on non-heterosexual sexuality transitions. The main research questions are as follows

To explore how young males experience non-heterosexual sexuality

transitions within a family context

To explore how young males experience non-heterosexual sexuality

transitions within a friendship context

To gain insight into the extent in which social context influences non

heterosexual sexuality transitions

To obtain an understanding of the risk and protective factors associated with

this transition

1.5 Outline of the study

Chapter One

introduces the research topic and the context, rational and main aims and objectives of the research are presented

Chapter Two

presents the reviewed literature relevant to the research question. In order to examine the different aspects with potential relevance to this study both national and international academic books and journal articles were consulted. Chapter Three outlines the methodological approach of the research and the rational and strengths and limitations of the chosen research design. Ethical considerations will also be explored along with the approach taken in relation to data collection and analysis

Chapter Four

presents the findings of the study under the themes and sub themes which emerged as part of the data analysis and coding process

Chapter Five

links the findings with the overall aims of the study. Findings are discussed in relation to reviewed literature and reflection on the process of the study is presented.

Chapter Six

puts forward conclusions that can be drawn from the present study. Recommendations in relation to further research and with regards to work with sexual minorities are also presented.

Chapter Two: Literature Review

As the objective of this research is to explore how non-heterosexual sexuality transitions are experienced this review will begin by exploring the literature in relation to the various perspectives on non-heterosexual sexuality transitions in general. The emerging discourse in relation to the significant influence of social context on this transition will follow. Due the family being one of the main ecological systems in which sexual orientation identity is explored (Bronfenbrenner, 2005) literature in relation to family contexts will then be discussed. Owing to the influence of friends already identified within adolescent developmental psychology (Graber & Bastiani-Archibald, 2001), the friendship context subsequently will be explored. Finally, this review will present the most relevant research pertaining to risk and protective factors associated with this transition.

2.2 Perspectives on non-heterosexual sexuality transitions

Research on sexual identity formation and the „coming out‟ process has been carried out for a number of years. Early theoretical frameworks recognised that one has to weigh up satisfying emotional and physical needs with the resulting stigmatization (Altman, 1971). Plummer (1975) was one of the first to develop a stage theory and recognised that an individual may never get past the stage of accepting the label and its potential consequences. Recent research signifies a shift away from the linear stage models of Plummer (1975), Cass, (1979) and Troiden, (1989) in favour of theories that are inclusive and take into account psychological, historical and socio-cultural factors (Eliason & Schope 2006; Kelleher 2009; Rivers 2002).

A vast amount of research in the area of sexual orientation has been carried out in recent years; psychological research in particular has grown immensely in the last decade (Patterson & D‟Augelli, 2012; Saewyc, 2011). It is now argued that identity development is better seen in terms of milestones rather than stages and the unpredictability among milestones means that there is no normal or „typical‟

developmental trajectory (Eliason & Schope, 2007; Savin-Williams & Cohen, 2007). The milestones identified include feeling different, experiencing same sex attraction, doubting ones heterosexuality, taking part in same-sex behaviour (this may never happen), self-identification, disclosure and acceptance. Disclosure to others may immediately follow self-disclosure or it may take years or even decades (Savin Williams & Cohen 2007).

Hammack and Cohler (2009) see identity as a process of co-construction between individual and culture. Considering the different historical, cultural and psychological perspectives in this area, they highlight the importance of taking an interdisciplinary approach to the study of sexual orientation. Developmental science has also recognised the importance of studying the influence of social and historical change over the life course (Cohler & Michaels, 2012).

Life course perspectives are considerably important when examining the lives of sexual minorities especially in light of the historical events and social changes that have shaped the particular experiences of different birth cohorts (Cohler & Michaels 2012). Seidman (2002) argues that the current cohort of sexual minority youth are more able to integrate their sexuality into their daily lives than previous cohorts. The rapid change in social climate surrounding the lives of sexual minorities means that findings of studies published in the past few years may in fact be based on an earlier cohort of sexual minorities and may not be applicable to the present cohort (Cohler & Michaels 2012). This poses major challenges to researchers in the area in terms of accessing up-to-date material and emphasises the importance of ongoing research in this area.

2.3 The influence of social context on non-heterosexual sexuality transitions

The „sexual transition‟ is shaped by psychological and contextual factors both of which can cause unique challenges (Leleux-Labarge, Hatton, Goodnight & Masuda, 2015). Adolescence and emerging adulthood are crucial times for sexual identity exploration and this occurs alongside the normal challenges of these times such as puberty, changing family and peer relationships, exam stress and career decisions (Arnett, 2006, Graber & Bastiani Archibald, 2001). Sexual minorities also face challenges unique to their status as a stigmatised group within society (Herek & Garnets, 2007). Society and social context is shaped by social norms, values and constraints (Graber & Bastiani Archibald, 2001). Therefore social, political and legal issues present young people with pros and cons with regards to confronting their sexual identity. One of the challenges they face revolves around common assumptions such as the presumption of heterosexuality and expectations of gender conformity. The fact that this transition occurs within a heterosexual society with heterosexual norms can lead to this group being invisible in society (Thompson & Jonson, 2003). They can be ignored or their behaviour or feelings considered a passing phase references. However, there is a growing awareness that it is a natural developmental outcome for some adolescents (D‟Augilli & Patterson, 2012).

A cultural ideology that is said to shape today‟s society is heterosexism. Herek (2004) describes this as an ideology that perpetuates sexual stigma by denying and denigrating any non-heterosexual form of behaviour, identity, relationship or community. Seidman, Meeks and Traschen (1999) state that heterosexism is institutional and cultural and not just a matter of individual prejudice. Social Stigma is learned and internalized through childhood socialization and this internalization can lead to people concealing their identity (Goffman, 1963).

Horn (2012) in her review of literature surrounding attitudes toward sexual minorities found evidence of considerable complexity. It was found that attitudes have changed in some important ways yet prejudice still exists. Modern prejudice is more covert and implicit and individuals can display both explicit positive attitudes and strong negative implicit biases towards sexual minorities at the same time (Steffens, 2005). For example although reactions may appear positive, social constraints may be imposed such as members of one‟s social network stating that discussions relating to sexual orientation and activity must be kept to a minimum. These constraints may represent an underlying negative reaction to one‟s sexual orientation and a desire for the individual to reject their sexual identity (Rosario & Schrimshaw, 2012).

Aspects of social context that have been found to correlate with higher levels of sexual prejudice include the degree of religiosity within a country, traditional attitudes towards gender roles and political ideologies (Horn, 2012). This is extremely interesting when considering Irish society as discussed in chapter one. Despite recent changes, ideologies of the Catholic Church are still prevalent in today‟s society (Ryan, 2003). This can be seen in the discourse that arose surrounding the referendum on same sex marriage with regards to the fear of the impact of gay or lesbian parents on children (Patterson, 2012). Reygan & Moane (2014) in their recent study of

religious homophobia in Ireland found that although Irish society is increasingly pluralistic, religion still presents significant challenges to LGBT people, such as eliciting feelings of guilt and shame. Baiocco et al.,(2014) also found that perceived ideologies from a strong religious culture can cause not only negative attitudes towards personal identity but also suicidal ideation.

Today Ireland is increasingly multicultural and influenced by individualism and global ideologies. According to Savin-Williams and Cohen (2007) the start of the twenty-first century has also seen prolific increases in gay youth culture and exposure. The authors claim „The media is increasingly celebrating their culture and characterising them as any youth (i.e., the girl/boy next door)‟ pp. 42. Lalor, DeRoiste & Devlin, (2007) also identified that there is growing acceptance of different sexualities within contemporary culture in Ireland. Yet, prejudice still exists and this is acutely illustrated in the fact that a recent Irish study found that LGBT youth consider this new societal acceptance of them as more of a tolerance than a celebration (Mayock, Bryan, Carr & Kitching, 2009).

Negative peer communication and instances of homophobia and harassment within educational settings have also been well documented within the international and Irish context (Bontempo & D‟Augelli 2002; MacManus 2004; Schubotz & McNamee, 2009). Youth often refuse to disclose their sexual orientation whilst at school due to experiences/fears of bullying or being singled out (Schubotz & McNamee, 2009). Other studies found school truancy and early school leaving to be a direct result of issues pertaining to sexual orientation (MacManus, 2004). Negative peer communication often becomes internalized and may cause feelings of self-contempt and self criticism, leading to social and psychological alienation and even internalized homophobia (Weinberg, 1972). A lack of opportunity to discuss non-heterosexual issues has been argued to contribute to the widespread homophobia in many Irish educational settings (Lalor et al., 2007; Lynch & Lodge, 2002).

There are multiple ecological social systems in which young people explore their sexual orientation identity including family, school and peer networks (Bronfenbrenner, 2005). Harper, Serrano, Bruce & Bauermeister, (2015) also put forward the idea of the internet as an avenue for sexual identity development. They found that today‟s youth use the internet for a range of functions relating to sexual identity development including increasing self-awareness of sexual identity and to gain support and affirmation of their sexual feelings (Harper at al., 2015). Hillier, Kudras and Horesley, (2001) highlighted the importance of the internet in reducing isolation and connecting sexual minority youth with others of the same orientation. This is an area that is gaining attention within research and will be particularly relevant to the current birth cohort of sexual minorities (Parsons & Grov, 2009, Silenzio et al 2009).

2.4 The experience of non-heterosexual sexuality transitions within a family

context

One issue that appears to be significant regardless of birth cohort is that of disclosing sexual orientation to one‟s family. Many studies highlight the fact that disclosing sexual orientation to family members is one of the most significant issues that sexual minorities face (Thompson & Johnson 2003, D‟Augelli, Hershberger, & Pilkington 1998, Goldfried & Goldfried 2001). Patterns of disclosure have shown that parents are rarely the first person to whom sexual minorities disclose and mothers are often disclosed to before fathers. Mothers are also a more common recipient of a disclosure than a father (Beals & Peplau, 2006; Savin-Williams & Ream, 2003). Alongside responses such as acceptance, there may be verbal or physical abuse, disownment, feelings of shame and denial (Lourdes 2003,GLEN/Nexus 1995). In some cases where adolescents receive negative reactions they may respond by running away, isolating themselves from others or becoming depressed or suicidal (Thompson & Johnson 2003). By contrast, when parents are accepting and supportive these youth are much less likely to exhibit many of the problems listed above and tend to have higher levels of self-esteem (Ryan et al, 2010).

Savin-Williams (2001) highlights the fact that the spectrum of parental responses to disclosures has been categorized by some as being similar to individuals undergoing grief and mourning for the loss of an identity that the parent had assumed for the child. Factors that have been found to influence parental response to disclosure include religiosity, political orientation, traditional attitudes towards gender roles and socio-economic status (Baiocco et al., 2014). Ryan et al., (2010) in their research on family acceptance and LGBT youth concluded that Latino, religious and low-socio economic status families were found to be less accepting of LGBT family members.

Concealment of sexual orientation is an option that may be chosen by some individuals in place of disclosure. Savin-Williams & Diamond, (2000) found that many sexual minority youth spend large portions of their adolescent years hiding their sexuality from their parents. Reasons for this include fear, expectations of rejection, discrimination, victimisation and harassment (Thompson & Jonson, 2003). Yet, at the same time it was found that hiding or „passing‟ is stressful and requires constant vigilance not to be found out (Eliason & Schope, 2007). Self-concealment is positively associated with psychological distress, suicidal ideation, depression and anxiety (Leleux-Labarge et al., 2015). It can lead to individuals leading a self protective double life, one known to their families and friends and one unknown (Rotheram-Borus & Langabeer, 2001). Avoidance can also lead young people to become engaged in relationships with members of the opposite sex (Lalor, et al., 2007). This can in turn lead to challenges in keeping their two lives separate, such as emotional conflict brought on by self-doubt, self monitoring and self-denial (Rotheram-Borus & Langabeer, 2001). Concealing sexual orientation can also deprive young people of valuable support networks (Schubotz & McNamee, 2009) Disclosure conversely can have both immediate and long-term implications for individuals (Beals & Peplau, 2006). Along with negative responses disclosure can also lead to social support, self-acceptance and improved self-esteem (Savin-Williams & Cohen, 2007). D‟Augelli, Hershberger and Pilkington (1998) found that unlike many parents sibling reactions are generally accepting. It is important to note that initial responses to disclosures can change and families often gradually adapt and resume supportive relationships over time (Savin-Williams & Reem, 2003). Recent research has found that disclosure can in fact strengthen relationships between individuals and their social networks (Beals & Peplau, 2006)

2.5 The experience of non-heterosexual sexuality transitions within a friendship

context

Friends and peer networks are another critical aspect of the interpersonal lives of sexual minorities (Rosario & Schrimshaw, 2012). Research has identified that peer reactions are perceived as being more accepting than parents and that the quality of relationships between peers and sexual minorities remains unchanged after disclosure (Beals & Paplau, 2006). Friends were also cited as the recipient of the majority of individual first disclosures (Beals & Paplau, 2006). Numerous studies have found that individuals receive more support from friend networks than family (Szymanski, 2009; Mayock et al, 2009).

In Mayock et al‟s (2009) Irish study, friends emerged as the most commonly cited source of support and trusted friends were particularly important during the coming out process. Colemen (1982) states that acceptance from heterosexual friends may be more valuable in the struggle to reverse negative self-images than acceptance from sexual minorities. Yet, Rosario & Schrimshaw, (2012) found that sexual minority youth may benefit more from having sexual minority friends than heterosexual friends. Literature in the area of sexual minority friends has only recently begun to emerge and requires further attention. The supportive role of friends as a protective factor in this transition will be discussed further in the following section.

2.6 The Risk and Protective factors associated with this transition

With regards to mental health and sexuality transitions international research has found higher rates of psychological distress and suicidality in sexual minorities due to victimisation, verbal and physical abuse and lack of social support (Adams, Dickinson & Asiasiga, 2013). Meyer, (2003) found that non-heterosexuals were twice as likely to have a mental health disparity than their heterosexual counterparts. According to Herek (2004) sexual minorities can experience psychological difficulties as a consequence of accepting society‟s negative evaluation of them. A number of studies have shown that sexual minority youth may be at greater risk for poorer school outcomes, multiple suicide attempts, emotional distress, risky sexual behaviour, delinquency and substance use (Elze, 2005).

Meyer‟s (2003) minority stress theory proposes that the stigma, prejudice and discrimination experienced as a result of sexual minority status in turn leads to stress which causes health disparities for this particular group. Hatzenbuehler (2009) in his integrative psychological mediation framework ads to the minority stress theory by incorporating the mediating factors of general adolescent vulnerabilities such as maladaptive coping and cognitive processes. This innovative work highlights the importance of incorporating knowledge already available in the area of adolescent development to the study of sexual minorities.

Elze, (2005) and Mayock et al., (2009) found that many individuals display resilience in the face of stigmatization. In fact, many authors discuss the need to identify protective factors rather than focusing solely on risk factors, as this can lead to a misrepresentation of the lives of sexual minorities (Savin-Williams, 2001; Mayock et al., 2009). Acknowledging sexual minority youths‟ capacity to successfully negotiate this transition and their life circumstances has been recognised as a gap in both international and Irish literature (Mayock et al 2009).

One protective factor that has been the topic of much research is that on the role of supportive relationships (Bontempo & D‟Augelli, 2002). However findings on the effectiveness of support have been inconsistent. Bontempo and D‟Augelli (2002) found that family support may protect the youth‟s mental health from the effects of victimisation. However Szymanski (2009) found that the availability of support did not moderate the levels of sexuality stress and psychological distress. Mustanski, Newcomb and Garofalo (2011) also found that social support did not alleviate the negative effects of victimisation.

Recent research by Doty, Willoughby, Lindahl and Malik, (2010) identified the conflicting findings relating to the impact of social support on sexual minorities and decided to look specifically at sexuality related social support. They found that support for stress relating to their sexuality was less available than support relating to other stressors and that sexual minority friends in particular provided the highest levels of support relating to sexuality stressors. A limitation of many earlier studies is that they fail to differentiate between friend categories when looking at this issue. Literature has identified that alongside support other protective factors include personality, social competence and social context (Luthar & Cicchetti, 2000). Although sexual minorities face stigmatization from families, peers and communities most successfully navigate this transition and attain similar levels of health and wellbeing than their heterosexual peers (Saewyc, 2011).

2.7 Conclusion

This chapter has examined literature in the area of non-heterosexual sexuality transitions and the influences on this transition. Research has highlighted the variability in developmental pathways and individual nature and in which this transition is negotiated. Individual, socio-cultural and historical factors all need to be considered when exploring this transition due to their multiple levels of influence. Family and peer contexts where found to be critical contexts for identity development to take place. The increased risk for mental health disparities and associated problem behaviours in sexual minority youth has been well documented but the need to

explore protective factors and resilience is a clear gap in existing literature.

Chapter Three: Methodology

3.1 Introduction

This chapter is concerned with the methodological approach of the study. The approach chosen will be discussed in detail alongside the rationale, and strengths and limitations of the approach. It is of paramount importance to align the methodological approach with the aims and objects of the research (Silverman, 2010). The aim of this study is to gain insight into the retrospective views of non-heterosexual males aged between twenty-five and thirty-two who are identifying as gay and who have gone through the majority of the elements associated with a non-heterosexual sexuality transition, such as self-identification and disclosure to others. The objective is to gain a deep understanding of the perceptions, experiences and interactions of this group in order to identify and explore influences on this transition and how the transition is negotiated.

There was careful consideration of a number of methodological approaches before deciding on an approach influenced by interpretive phenomenology. There were various reasons for this choice such as it being advocated as an approach suited to the study of sexuality by many researchers in the area (Smith, Flowers & Larrkin, 2009; Frost, McClelland, Clark & Boylan, 2014). The fact that this approach is concerned with the details of participants‟ lived experiences as well as well as how they interpret that experience (Frost et al. 2014 ) clearly aligned it to the aims and objectives of this study.

3.2 Research Design

The study adopted a cross-sectional design. A qualitative phenomenological approach was chosen as it was felt that this method was most appropriate in terms of the research problem being investigated. The rationale for choosing a qualitative approach was that it would allow for the attainment of detailed data and the examination of complex interrelationships, which opting for depth of coverage is more suited to (Denscombe, 2014). Qualitative research allows for a degree of flexibility and potential for development and these are important elements of this research design, as research participants may identify emerging issues that are important to them and these issues or themes can then be explored in more detail. This participant focused approach is the reason why semi-structured interviews were chosen. Interviews are also considered one of the best ways of gathering in-depth data especially if the research aim concerns gaining insights into feelings, perceptions and experiences (Denscombe, 2010).

According to Frost et al., (2014), phenomenological methods are essential in the study of sexuality as they allow the researcher insight into how the phenomenon of sexuality is experienced in everyday life and, moreover, they allow for the diversity of individuals‟ experiences to be captured. Interpretivism is an epistemological position

that is concerned with grasping subjective meaning (Bryman, 2012). This approach is in direct contrast to positivism, which applies a scientific model to the study of the social world (Bryman, 2012). Positivism assumes that reality is objective and can be separated from the observer and can, in turn, be measured and predicted (Biggam, 2009). Interpretivism, however, emphasises understanding human behaviour and argues that people and their institutions are fundamentally different to the subject matter of the natural sciences and therefore require a different logic of research procedure (Bryman, 2012). Interpretivism acknowledges that there are many, equally valid, interpretations of reality (Biggam, 2009).

An Interpretive Phenomenological Approach (IPA) was also chosen as it prioritizes the viewpoint of the participant along with utilizing analytical strategies in order to examine the social, cultural and political climate in which the data emerged (Frost et al., 2014). This combination of analytical and descriptive components allows for experiences to be compared across individuals and across periods of time. As this is a retrospective study, looking back at the how individuals experienced different elements of the transition, this element is of particular significance.

3.3 Strengths and Limitations of Methodological Approach

Although opting for a qualitative phenomenological approach allows for the details and richness of peoples lived experience to be captured, due to the small sample size findings are not generalizable. This is a considerable limitation and it is acknowledged that quantitative research has an advantage in that it can often be more representative and generalizable (Bryman, 2012). A further limitation of qualitative

research is that it can be quite difficult to replicate (Sarantakos, 2013)

Positivism and interpretivism both have strengths and limitations. The aim of a positivist approach is to generate findings that are valid and reliable (Silverman, 2010). Although this is important, it has been argued that due to the fact that human subjects are so closely interconnected with their social context and setting, it is impossible to present social facts as independent from these (Husserl & Heidegger as cited in Breakwell, Smith and Wright, 2012). A strength of the IPA approach is that it recognises that research is a dynamic process in which the researcher and participant play an active role (Breakwell et al.,2012).

3.4 Sample

Males alone were purposefully chosen for this study as it was felt that it would not be possible to compare both male and female experiences within the time limits of this research and literature has already identified many differences in experiences of both male and female groups (Diamond, 2008; Katz-Wise & Hyde, 2014). The age group of 25-32 years was chosen so as to target males identifying as gay that have gone through many of the milestones associated with this transition so that they can reflect on past experiences. Due to ethical considerations it was also felt that a younger age group may be more sensitive to the issues being discussed as they might still be very much in the midst of the transition. A recent study in Ireland found that the average age at which one disclosed their sexual orientation to others was twenty-one (Mayock, et. al., 2009) and this fact helped justify the decision for the chosen age group. Purposive sampling identified seven participants and even though numerous potential gatekeepers were contacted such as Belongto, Gay and Lesbian Equality Network, (GLEN), and various other LGBT societies none of these avenues proved fruitful. This fact highlights the hard to reach nature of this particular group. A combination of purposive and snowball sampling, a technique often considered when exploring sensitive issues (Mayock et al, 2009) was utilised. Using snowball sampling alone may have led to initial contacts shaping the entire sample (Burnett 2009) but the researcher strove to ensure diversity within the sample.

3.5 Research Instrument

According to Mayock (2009), qualitative interviews are an ideal instrument for investigating the contexts which influence the lives of sexual minorities. According to Smith (2007) semi-structured interviews allow for initial interest areas to be expanded upon or moved away from in light of the participant‟s responses. Structured interviews on the other hand are more restricted and categories are predetermined in advance in order to elicit what constitutes as the required data to be obtained (Smith, 2007). Other qualitative methods of data collection were considered such as focus groups, however due to the sensitive nature this research it was felt that this would be inappropriate as it could possibly cause discomfort to some participants. Having decided on semi-structured interviews an interview schedule was developed (see Appendix A). Extensive literature in the area was explored in advance of compiling the interview schedule in order for initial categories of interest to be identified. This was invaluable as it allowed for previously identified influences on this transition to be included. It also allowed for limitations in previous research to be identified so as that these could be avoided as far as was possible in this research. Due to the exploratory nature of this research the interview topics were open and gave considerable scope for participants to elaborate on influencing factors.

The topics were then ordered in sequence taking into account which topics may be interlinked and which may naturally be discussed together. A strategy that was employed was to encourage the participant to speak with as little prompting as possible. Using this technique avoided situations in which participants were led by questions (Smith, 2007). In order to test the research instrument a pilot study was carried out.

3.6 Pilot Study

The pilot study firstly involved seeking information as to whether the letter of explanation was understood. This is of fundamental importance as it impacts on the willingness of people to participate in the research and the data that will be collected (Breakwell et al., 2012), The pilot interview allowed for comprehension of questions to be tested as well as introduction, sequence and level of comfort with questions to be examined. It also tested the appropriateness of the tool in relation to including questions surrounding previously identified influences and the information obtained from the questions with regards to their relevance. Feedback on these issues was then taken into consideration and the necessary amendments were made.

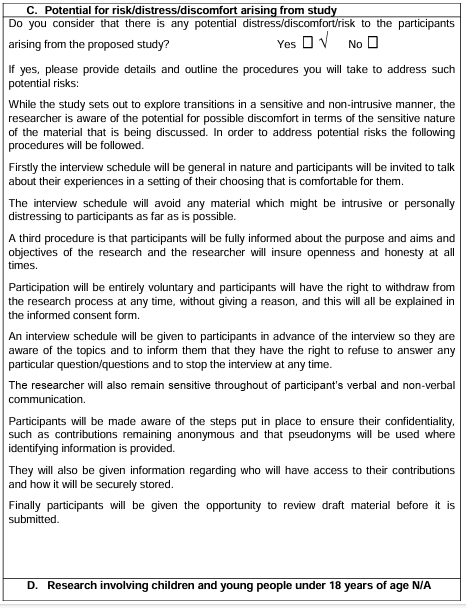

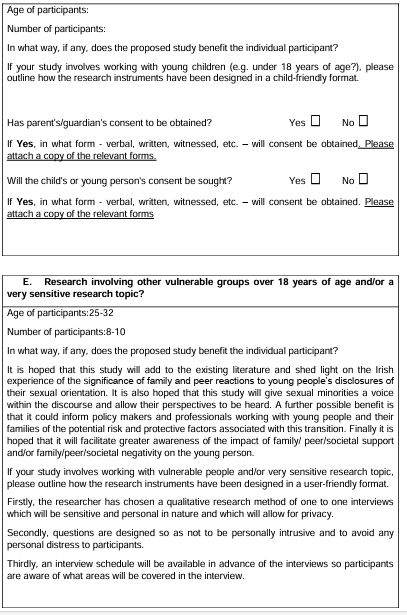

3.7 Ethical Issues

Ethical considerations were given significant attention. Prior to carrying out any research in the field ethical approval was sought and granted from Dr. Kevin Lalor, Head of School of Languages, Law and Social Sciences. While the study set out to explore transitions in a sensitive and non-intrusive manner, the potential for possible discomfort in terms of the sensitive nature of the material that was being discussed was acknowledged. Silverman (2010) identified three ethical issues that need to be considered when conducting social research. These are informed consent, sensitivity towards research participants and anonymity and confidentiality. In order to address these issues and any potential risks the following procedures were be followed. Firstly, a qualitative research method of one to one interviews was chosen as this allowed for privacy and sensitivity (Mason, 2001). The interview schedule was general in nature and participants were invited to talk about their experiences in a setting of their choosing that was comfortable for them. The interview schedule avoided any material which might have been intrusive or personally distressing to participants as far as was possible. A third procedure was that participants were fully informed about the purpose and aims and objectives of the research. Participation was entirely voluntary and participants had the right to withdraw from the research process at any time, without giving a reason, and this was explained in the letter to participants (See appendix B) and informed consent form (See appendix C). A letter explained the purpose of the research was also sent to potential gatekeepers (See appendix D). An interview schedule was given to participants in advance of the interview so that they were aware of the topics and to inform them that they had the right to refuse to answer any particular question/questions.

Participants were made aware of the steps put in place to ensure their confidentiality, such as contributions remaining anonymous and pseudonyms being used where identifying information was provided. The researcher recorded interviews on a Dictaphone and transcribed them at a later stage. Once transcribed contributions were stored on a password protected computer and only the researcher had access to the information gathered.

Ethical issues identified with regards to clinicians working with sexual minorities were also transferred when looking at the role of the researcher. Wirth (1978 as cited in Thompson & Johnston 2003) stated that evaluation of one‟s value system is required in order to ensure sensitivity to the situations sexual minorities face in society. The researcher acknowledged that issues such as subjectivity and reflexivity needed considerable attention throughout the research process. This allowed the researcher to reflect on her role, position and biases and how these may impact on the quality of data collected and the way in which it was interpreted (Robert-Holmes 2014). For further ethical considerations see ethical application form (Appendix E)

3.8 Data Analysis

All recorded interviews were transcribed as close to the interview date as possible, with notes on tone and non verbal reactions also recorded (See Appendix F for sample interview). Transcripts of the interviews were then analysed case by case through a systemic qualitative analysis. Data was catalogued and indexed, which allowed for recurring issues or themes to be identified and coded (See Appendix G for sample coding). A combination of describing emerging themes and interpretative analysis of those themes took place in order to present an understanding of what elements of the experience mattered to participants and also how it mattered. These identified themes and patterns were then used to guide the presentation of findings.

Chapter Four: Findings

4.1 Introduction

The chapter presents the findings of the study under the themes and subthemes which emerged as part of the data analysis and coding process. The themes identified included the experience of non-heterosexual sexuality transitions within a family context, the experience of non-heterosexual sexuality transitions within a friendship context, the impact of personality and personal traits on young people‟s sexual transitions, the influence of social context on young people‟s sexual transitions and self-identified risk and protective factors in relation to sexual transitions.

4.2 The experience of non-heterosexual sexuality transitions within a family

context

The study found that families impacted the transition in both positive and negative ways. Due to the varying reactions and impact of different family members, findings are broken into the influence of mothers, the influence of fathers, the influence of both heterosexual and non-heterosexual siblings and the impact the transition had on relationships with family members.

4.2.1 The experience of disclosing to mothers

The study found that mothers had both positive and negative reactions to their son‟s disclosures but it is important to note that negative reactions came in different forms and there were a number of perceived reasons behind these reactions. Influencing factors included mothers fearing for the lives their sons had ahead of them due to society‟s views on non-heterosexual people. The negative reaction was not always towards the person but towards society.

“She cried, but she more cried about not the fact that I was gay, it was more

about the fact of how society I suppose back then …would have treated

individuals like me and like people heckling me down the street and I suppose

people‟s views and that in general”

(Interviewee 3)

One internal factor that influenced a negative reaction was due to a misunderstanding around sexual orientation and thinking that this decision was chosen. This in turn put a strain on the mother son relationship and the atmosphere in this house.

“Mam was shocked, … I don‟t think she understood it properly initially, it

was a bit tough for a while, … I remember Mam saying to me one night, „when

did you decide this‟, and I was trying to explain that I didn‟t, I didn‟t decide

this”

(Interviewee 5)

Mothers in particular were perceived to be upset by the shock and the fact that they had not known or had not anticipated that their sons might be gay due to their sons being in heterosexual relationships,

“so like my Mam was obviously like the one that had the worst reaction, it was

kind of because I was seeing a girl and then not seeing a girl, I mean so she

didn‟t know what was going on‟.

(Interviewee 3)

4.2.2 The impact fathers on non-heterosexual sexuality transitions

The study found that although fathers had an unwillingness to talk about issues relating to sexual orientation, this silence on the issue was perceived in a positive way. No participants appeared to be hurt or put out in anyway about the fact that they don‟t discuss these issues with their fathers. The one or two occasions where the issue was brought up in a light-hearted fashion made participants aware that it was known and acknowledged at least and that appeared to be enough.

“he used to use these little expressions like are you going a bit funny or

(laughs) he‟d say to me like these little phrases that he knew I‟d react to but I

knew that he was comfortable with it but it was just something that he didn‟t

really want to speak about”

(Interviewee 7)

Only two participants told their fathers of their sexual orientation directly, others were told by other family members or left to figure it out for themselves. One of the participants who did tell his father directly acknowledged that fact that it was harder to tell his father than his mother and tried hard to understand and make sense of his father‟s thought process on the matter which illustrates the complexity of father -son relationships.

“I‟m not really sure why it was but my Dad was way harder, it actually took

three attempts… he took it well but not great … I think there might have been

a bit of misunderstanding as to his role in it, was it his fault ya know cause he

wasn‟t really there, I don‟t know if they are the reasons but he was very

reflective … it took him ages to say words out loud about it”

(Interviewee1)

4.2.3 The influence of heterosexual and non-heterosexual siblings

The study found that disclosure to siblings can be as big a concern as disclosure to parents, and over half of participants told siblings before parents. Disclosure to siblings can be an issue regardless of whether there is an assumption that they will be undoubtedly supportive.

“yeah I always knew that she would be supportive completely, it was never a

question of it being any kind of an issue, still a big deal at the time for me to

say, like the words out loud to somebody else but like I always knew it would

be totally totally fine”

(Interviewee 6)

The study found that sibling reactions in general tended to be accepting and that the influence of non-heterosexual siblings was more significant than that of heterosexual siblings and therefore the following section will focus on this. Participants having non-heterosexual siblings affected the transition in various different ways. In a positive way in that having older siblings can ease the coming out process to the point where it was felt that disclosures were unnecessary and this occurred regardless of the fact that older siblings‟ transitions had been difficult.

“I just never felt the need or pressure of coming out, I don‟t know if that was

eased by the fact that my brother and sister who are both gay, had a little bit

more of a rougher transition than me but yeah I just never felt the need to

come out…. I never told anyone and then I just brought my boyfriend home”

(Interviewee 7)

The study also found that having other non-heterosexual people in your life can help discredit and breakdown stereotypes,

“I just found it really influential that like there‟s no, it was like the stereotype

wasn‟t there, the stereotype I had in my head wasn‟t necessarily true”

(Interviewee 7)

But finding out later on in life that younger siblings were gay and not having realised this while disclosing to them can have a negative impact later on.

“for a sixteen year old there was no negative reaction, … but in retrospect he

probably would have been gay at the time as well so that‟s a bit of a sad issue

for me to deal with cause he obviously has his own coming out story but when

I look back at his struggle I was blinded because I was so involved with myself

I didn‟t realise it”

(Interviewee 1)

4.2.4 The impact on relationships with family members

Most family relationships were influenced in a positive way by the transition, if not immediately then over time,

“your relationship just feels stronger cause they‟re accepting you for who you

are…it changed cause it was like I could be more myself around them”.

(Interviewee 7)

For some the initial period after disclosure was difficult but the supportive relationships eventually resumed. The study found that the transition‟s impact on relationships can be mediated by coinciding changes in behaviour, outlook and the life style of the individual at the time. When speaking of the impact on the relationship with his sister one participant stated,

“well I imagine who I was wasn‟t a very nice person at the time, I would have

gone from a person that was family orientated to someone who was the

complete opposite … I was just on mad ones all the time which isn‟t ideal for

anyone from a family point of view but I just wouldn‟t have seen outside that

bubble at the time”

(Interviewee 1)

One participant‟s experience with his father was quite difficult and disclosure led to a physical altercation.

“My Dad took it really bad, I had a fist fight with him, he caused murder in

the house and was telling me to get out of the house”

(Interviewee 2)

Yet, it is important to note that the relationship was strained before disclosure also and that even after a period of not speaking for three years the relationship is better now than it ever was. When asked about whether disclosure changed his relationship with his father he stated,

“completely, (then changed his mind), no I wouldn‟t say it did, if

anything…when I think back its made it a lot better because the person

(paused), I never really got on with my Dad, we didn‟t speak, I lived with him

for three years after that and we didn‟t speak at all and before I didn‟t have a

great relationship with him cause all me anger would come out in the house….

Now I‟ve a better relationship with me da than I’ve ever had in me whole

entire life”

(Interviewee 2)

4.3 The experience of non-heterosexual sexuality transitions within a friendship

context

Friends in general were found to be accepting and supportive and in the following section non-heterosexual friends in particular will be looked at in more detail due to the significant findings in terms of their impact. The fact that many individuals switched friendship groups as part of this transition will also be explored.

4.3.1 The impact of having non-heterosexual friends

Participants with other non-heterosexual friends in general cited this as a great support as they felt that the journey and experiences could be shared amongst people that knew what you were going through. Also having new experiences for the first time was easier when they were firsts for those with whom you were experiencing them.

“it was eased by the fact that there was a few of us going through the same thing and going on a bit of a journey together so like the first time we ever went to a gay bar was together, the first time we all went on a gay weekend we were all together so those kind of things made it much easier”

(Interviewee 7)

The study also found that having non-heterosexual friends can have a negative impact in that they can put unnecessary pressure on individuals to come out to others before they‟re ready.

“I think I said to him that I might be or something like that, he was

gobsmacked and was straight away, „awh you are if you think like that‟, I

wouldn‟t say he was supportive, it was more of an excitement for him … I felt

that he was more pushing me out”

(Interviewee 2)

4.3.2 Switching friendship groups and its impact

A number of participants discussed switching friendship groups as part of this transition and cited many reasons for this. Switching friendship groups had positive outcomes for many as they realised that who they had perceived as friends might not have been actual friends at all. Moreover, the reason they had persisted in staying with this group could have been through fear of being seen as different or to mask their sexual orientation.

“All my friends were the friends that would slag everyone, they‟d be like

they‟re fagots and this and that…, they were proper macho scumbags and like

there was times when I didn‟t even want to be with them and I used to prove myself to them, just so people would think that I was more macho than I actually was ”

(Interviewee 2)

Others in hindsight noted that they could have done more to maintain relationships with heterosexual friends who they did not incorporate into their new lifestyle.

“I am a bit disappointed that I didn‟t make the effort to ya know stay friends with the people that were my rock when I was younger but some of them did come out with me to gay bars and stuff but I just never went to straight bars then, ever!… it wouldn‟t even enter my head to accommodate straight friends

anymore”

(Interviewee 1)

Switching friendship groups as part of this transition also had a negative influence on some as they were introduced to a different lifestyle, one associated with the gay scene.

“I had actually shifted from one group of friends, all my school friends to another group, I started going out with gay friends, not people that I knew that well and with these people, I started taking drugs… I remember disappearing and coming back in bits”

(Interviewee 1)

Being introduced to other non-heterosexual people and the gay scene also had positive effects for some in that it helped broaden perspectives on what being gay might be like and diffuse negative associations.

“cause you grew up thinking gays were disgusting, men and women marry, you grew up and had kids and then when I started going out with (gay friend) and his friends I started to think this is actually not as bad, seeing how happy everyone was and all”

(Interviewee 2)

4.4 The impact of personality and personal traits on young people’s sexual

transitions

The study found that individuals had very different approaches to coming to terms with their sexuality and feelings of difference. Some utilized personal coping mechanisms such as telling themselves it will be ok or allocating time to think about the issue whereas others felt the need to focus more on concealment and doing everything in their power not to be found out.

4.4.1 The impact of personal coping mechanisms and personality traits

During the period of uncertainty around their sexual orientation some participants had the ability to push feelings of difference and the idea that they might be gay aside and not let it consume them.

“it was something that might have popped into my head the odd time and it was something that you could kind of push to the back of your mind, it was never something that took ever me head ”

(Interviewee 6)

Whereas others could not do this and thought about it every day and constantly worried about it due to an overwhelming sense that it was wrong.

“I used to think as a child that, you‟ll grow yourself out of it … but it never went away, it just got worse and worse and I thought about it more and more every single day. I thought at the back of my mind that this was wrong so I kept telling myself that you‟re not that forget about it”

(Interviewee 2)

One used a coping mechanism of allocating time to thinking about the issue of sexual orientation rather than it being constantly present in his mind

“I used to think about it often when I ran … whenever I‟d go running it was kind of like my head space, that was the time I kind of allocated myself to think about it (being gay)”

(Interviewee 7)

Some participants had confidence in themselves and believed that things would work themselves out. This confidence not only came from the individual having a supportive social network but also having a sense of inner confidence,

“I always knew that if it ever was an issue with anyone that I would have people to stand up for me and for myself as well I never felt weakness or that …I had my own kind of self-assurance and self-confidence that even if it was something that was reacted negatively too it was something that I could totally handle‟

(Interviewee 6)

4.4.2 The impact of concealing sexual identity

Concealing sexual orientation appeared to have a major impact on some people‟s lives but not on others. It affected people whether they had the ability to conceal or not. Some were able to conceal to the point where disclosure was a huge shock to both family and friends, yet the effort involved was a lot to bear.

“My whole entire life I felt the need to lie to people, sure I was with girls my entire life (up until coming out) … I convinced myself that that was the norm where deep down I hated it, during my relationships with girls that‟s what I thought of every single night (being gay)”

`

(Interview 2)

Concealment involved taking on different personas and was closely linked to fears of how others would react. It involved doing things that one may not have done otherwise in order to fit in and not be found out. Taking on different personas was perceived as being a coping mechanism.

“I used to prove myself to them, just so people would think I was more macho

than I actually was…to be more a boy, even down to the way I dressed ”

(Interviewee 2)

“I was with girls obviously growing up … but the whole idea is that you just try and cover it up so you do everything possible so you‟d hang around with the lads and do what the lads do”

(Interviewee 3)

This association with being and acting „macho‟ in order to fit in and be seen as straight was a common thread alongside the notion of gay being associated with being „girly‟. This highlights the impact of underlying stereotypes.

4.4.3 The importance of the reaction of others

How participants felt that others would react to the news of them being gay also linked with personality traits in a sense and how comfortable individuals were with themselves. For example, some people cared greatly about what others thought, whereas others were not concerned and felt that the experience was personal.

“it was about everyone but myself, I never thought about myself once, it was more about what everyone would think”

(Interviewee 2)

“their reaction and how they felt about it wasn‟t something that was ever really a big concern for me, I really did think this is my thing, this is part of me and my life and ya know it (what other people thought) just wasn‟t really something that crossed my mind‟

(Interviewee 6)

4.5 The influence of social context on young people’s sexual transitions

School was found to be a major obstacle in the coming out process. Media coverage at the time and the influence of the Catholic Church both contributed to a lack of exposure or discussion around sexual orientation which, in turn, reinforced hetero normative ideologies.

4.5.1 The school environment’s influence on the transition

Whether or not individuals „came-out‟ at school this study found that its influence on the transition was monumental. Those who could chose not to come out at school, and in fact no individual willingly came out in school. One individual knew that it would be instantly easier once he got passed his school years.

“I remember thinking ya kind of just need to get passed the, like, leaving school time and it will be so much easier cause at the time for a student to come into my school and say they were gay would have been soooooo controversial and would be such a big deal so that wasn‟t something that I had any intentions of doing whatsoever”

(Interviewee 6)

The study found that being victimised in school lead to school truancy and mental health issues.

“now I did get a hard time in school, it wasn‟t easy at all so I‟m actually quite proud that I did finished school considering the level of bullying and harassment that I did get”

(Interviewee 4)

One participant noted the lack of skills and training that teachers had in the area of homophobic bullying and its impact on mental health and the negative impact that this had on him. He also noted the unwillingness of teachers to address the situation. He put these factors down to a number of things such as the lack of knowledge and training on behalf of the teachers and also the school having a catholic ethos.

“Yeah they would pull people up over bullying me but no one ever got suspended, it was just a quick chat and that was it. Again I think they were afraid to deal with it …I don‟t think it was their fault, it was the education system at the time, ya know there was no training, obviously I was in a catholic school”

(Interviewee 4)

4.5.2 The influence of the media and the internet

It is important to note that at the time of this transition for participants the media coverage and content was quite different from today. All participants cited few or no shows containing gay storylines, issues or characters.

“there was no sitting down at the telly and watching any gay characters cause there was none”.

(Interviewee 4)

This impacted the transition in many ways such as reinforcing hetero normity and reinforcing stigma and isolation.

“it made you think that you grow up, you marry a woman and you have kids so that was drilled in your head, if you thought anything opposite to that you weren‟t right, you were sick”

( Interviewee 2)

The internet was used by some for various reasons. Despite differences in the availability and complexity of technology, the study found that a key area in which the internet aided the transition was through exposure. Allowing people to be aware of, and get in touch with, other non-heterosexual people. It helped break down barriers, build relationships and support networks and dismantle feelings of isolation.

“I remember going online to chat rooms and stuff like that and finding out where there other people like myself out there cause this was all new to me”

(Interviewee 4)

“I do think social media helped people to come out, I think it was easier for people to come to terms with the fact that they were gay cause all of a sudden there were so many more gay people out there, it made people‟s perceptions of it so much more acceptable”

(Interviewee 7)

4.5.3 The influence of the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church not only acted as a powerful tool and influencing factor in instilling the ideology that homosexuality was wrong it also played a major role in reinforcing heteronormative values and beliefs.

“people obviously wanted to live up to their faith so if the Catholic Church denounces homosexuality ya know that kind of is putting people in an awkward position”

(Interviewee 4)

“the church was teaching, you grow up, you marry a wife and you have kids so automatically you‟re thinking, I‟m gay, I shouldn‟t be here and then it‟s just drilled into your head especially with the Catholic Church”

(Interviewee 2)

4.5.4 The influence of specific communities

The fact that issues of sexual orientation were not spoken about in communities added to the isolation and stigmatisation. The underexposure of gay people in communities led to individuals who were gay or perceived to be gay being targets due to their minority status and people having a fear of the unknown or the different. Using the word „Gay‟ in a derogatory fashion and other associated terms appeared to be the norm and extremely common in certain communities.

“I think a lot of it had to do with how underexposed it was at the time and how it wasn‟t spoken about in schools and all that kind of stuff whereas now I think it makes it easier for young people to come out”

(Interviewee 7)

“when I was younger there was no positives to it, it was all negatives. It would only ever be used as a slagging that someone was gay ..it was the worst thing that you could be”

(Interviewee 1)

A number of participants commented on the class status of their areas and how being from a working class area had a negative impact on the transition. Participants stated that this was due to people in their areas being undereducated in the area of sexual orientation.

“with being from an area that would have been considered a little bit more working class and like people I suppose in a way in certain areas they were undereducated when it comes to the whole gay thing …so when you saw somebody that was a little bit different walking towards you down the street, yeah we were jeered and taunted”

(Interviewee 7)

4.6 Self-identified risk and protective factors in relation to sexuality transitions

Both risk and protective factors were found to be individual in nature and significant challenges in relation to this transition spanned a wide range of experiences. Support also came in various forms, with friends being the most widely cited source of support.

4.6.1 Challenges in relation to mental health

The significant impact on young people‟s mental health was emphasised by participants in a number of different ways causing anxiety, stress, depression, poor self-esteem, distraction and suicidal thoughts.

“I grew up a very unhappy person … I didn‟t want to live and I didn‟t like myself and it got to the point where I thought you either kill yourself and die or deal with the situation”

(Interviewee 2)

These issues had far reaching effects including causing individuals to drop out of college, school truancy, drug taking and absenteeism from the workplace.

“I told all of them in college and I left. I was kind of finding myself and I was too distracted that‟s why I left college, my mind-set wasn‟t there”

(Interviewee 1)

This double stigma at the time of having mental health issues and being a sexual minority was also highlighted. This subsequently led to feeling further isolated and hiding these issues from friends and, in turn, preventing another possible source of support.

“There were days were I used to lie in bed and cry myself to sleep but people didn‟t know that because I didn‟t show it it I remember going down to the doctor and I was on anti-depressants for about for years but nobody knew because I was ashamed of it”

(Interviewee 4)

4.6.2 Further associated challenges and risk factors

When asked about the biggest challenge of the transition or the most difficult period, different aspects were significant to each individual. One participant found that at one stage he felt as though he was living a double life and found this aspect the most difficult to deal with.

“… at that point nobody knew I was gay , it was kind of like … you‟re living a double life then I started seeing someone more regularly and I suppose that was probably the most difficult part because you‟re not experiencing it to the full extent of what it could be until you‟ve incorporated friends and family ”

(Interviewee 6)

Another participant developed a fear of catching HIV which had derived from a previous partner disclosing that he had tested positive. This in turn led to panic attacks and this had a huge impact on his life. Having accepted societies negative evaluation of non-heterosexual people one participant found admitting he was actually gay and trying to fit in with the gay lifestyle particularly difficult as he found that it wasn‟t what he had expected.

“Probably telling myself I actually was or being in a gay bar, probably going and actually being in a gay bar and thinking right this is what you‟re going to be and when I went to gay bars I wasn‟t into it and still don‟t really like it”

(Interviewee 2)

4.6.3 Further associated supports and benefits

Support came in different forms and was individual to each person‟s situation

although most participants noted that the best support came from talking with friends

and non-heterosexual friends in particular as also discussed previously.

“only a gay person would know what it‟s like to come out and most people have very different experiences of it but for us we were all going through it at exactly the same time ..ya kind of go through the same conversations so it really feels shared amongst people that really understand what‟s going on”

(Interviewee 6)

Two participants cited their place of work as a particular support but for different

reasons and to different extents. One due to the fact that it was an escape, where there

were people that cared and took an interest in their well-being.

“I think if I didn‟t have that job I wouldn‟t be here today … it was somewhere to go like, to get away from the shit I was dealing with in school ya know, I felt I could be myself, there was people there that I felt cared about me”

(Interviewee 4)

The other felt support due to the normalization and celebration of non-heterosexuality in the particular industry in which they worked.

“I think it‟s important for people to feel that they can be gay, it just so happens that I work in an area (fashion industry) that it‟s so openly acceptable, and this definitely helps”

(Interviewee 7)

A number of participants discussed the positive and reaffirming effects of the transition on one‟s mental health. They noted feelings of empowerment and self actualization after worries and fears had gone away.

“once the big disclosures were out of the way … ya can start to really be yourself and all of those confusing thoughts you had for years are totally gone, you feel great about it, you feel a real boost”